When senior facilities closed to visitors in 2020 to protect residents from COVID-19, the isolation of residents weighed heavily on outreach workers for the Nebraska Strong Recovery Project.

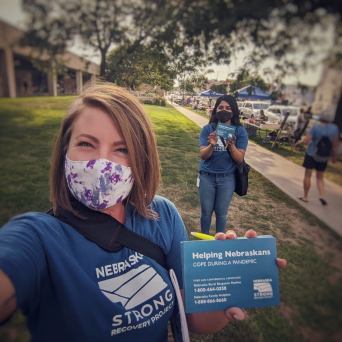

Charged with providing crisis counseling and other resources to help people cope with the pandemic, the outreach workers had to be creative to help some of the state’s most vulnerable.

In the early days, outreach workers connected by driving by long-term care homes and waving or holding signs or by doing “window outreach” using dry-erase markers and hands touching hands on each side of the glass, said Theresa Henning with Nebraska Strong’s Region 5 covering 16 counties in the southeast part of the state.

Once vaccinations opened the doors to visitors, outreach workers were quick to get inside senior residences to lead activities and hold group sessions to hear what’s going on. Henning said the requests for visits grew.

“They are so excited to have us come,” she said.

A resident of Lincoln’s Malone Manor senior living property said that’s true. She said the outreach workers “radiate friendship and love,” and residents will schedule birthday or holiday parties to be held when outreach workers are coming to make presentations or lead activities.

“It’s stressful, but when they’re here they get us relaxed,” the resident said. “Seriously, they make our day when they come. We love them.”

Smaller communities in the region weren’t always as receptive to an outsider coming in, Henning said.

“Fifteen of our 16 counties are rural with varying degrees of pandemic politics and acceptance of masks,” Henning said. “We spent a tremendous amount of time being persistent without being pushy – a hard balance – to build relations, and we’ve been really successful.”

The Nebraska Strong project originally formed after the state’s 2019 flooding. In 2020, it received $6.7 million in new federal grants to focus on COVID-19.

The project, scheduled to end in December, is a collaboration of the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, the University of Nebraska Public Policy Center, the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency and the state’s six behavioral health regions.

The pandemic turned out to be a disaster unlike any other, said Aaron Adams, network program specialist at DHHS’s division of behavioral health.

“Usually, a disaster affects very specific families or locations, but this was everyone, including the outreach workers themselves,” Adams said. “The scope was much broader than other situations.”

The project’s outreach workers, he said, “really rose to the challenge to find ways, whether virtually or in person, to support people.”

Adams said he was continually impressed by each regional team’s ability to be flexible and creative to adapt to the needs they saw.

COVID-19 is a polarizing topic, he said, and communities needed to be approached according to, for example, how open local businesses were to masked outreach workers and to displaying information about coping with the pandemic.

In many cases, outreach workers said, the common ground was a focus on stress and anxiety, whatever the source, and on paying attention to self-care and neighbors in need.

Region 5’s Nebraska Strong team, based in Lincoln, worked under the tightest COVID-19 restrictions, Adams said. The team had outstanding organization, communication and reach despite team members working remotely and not meeting each other for months, he said. Even then, the first meeting was outdoors.

When large group events resumed, outreach workers were there.

“Now we’re doing door to door,” Henning said. “We hope to reach some individuals we weren’t able to reach at events.”

Wherever outreach workers go, Nebraska Strong distributes a lot of printed materials, such as business cards, postcards, posters, flyers, brochures or children’s coloring pages. They advertise coping tips and the Nebraska Family Helpline (1-888-866-8660) and the Rural Response Hotline (1-800-464-0258). Both statewide hotlines will continue to offer support to Nebraskans after the grant supporting the Nebraska Strong Recovery Project ends on December 26.

When the team asks how someone is doing or if they know anybody who needs support, the person is more apt to talk about other’s needs than themselves, Henning said. They usually take the information, which they can share or use for themselves.

“They’re stressed, but feel that’s not as valid as someone else’s stress,” Henning said. “That fits the Nebraska culture of taking care of your neighbor and protecting your community.”

Author: Deb Shanahan